“Maybe A.I. can make a song that’s indistinguishable from what I can do. Maybe even a better song. But, to me, that doesn’t matter – that’s not what art is. Art has to do with our limitations, our frailties, and our faults as human beings. It’s the distance we can travel away from our own frailties. That’s what is so awesome about art: that we deeply flawed creatures can sometimes do extraordinary things. A.I. just doesn’t have any of that stuff going on. Ultimately, it has no limitations, so therefore can’t inhabit the true transcendent artistic experience. It has nothing to transcend! […] A.I. may very well save the world, but it can’t save our souls. That’s what true art is for.”

– from “Nick Cave on the Fragility of Life,” The New Yorker, March 23/2023

Like many lifelong writers, I have often been challenged by the idea that what I love most will never make me any money. So earlier this year, when I landed a full-time job as a writer for a creative studio specializing in artificial intelligence, disbelief featured prominently in the mix of emotions I felt.

The goal of my work is to infuse chatbots with personality – to bring “human” elements to artificially intelligent beings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the bulk of this work involves asking and answering questions. In real life, if we want to get to know someone, we might ask them questions. Their answers to our questions can help us understand who they are, what they value, and how they exist in the world. As long as they are answering truthfully, we can glean a great deal of information from a simple Q&A. Similarly, when it comes to programming a chatbot, the more questions you ask and answer, the more robust a personality you build.

I’m aware, most days, of the irony in writing for a company that could hypothetically teach AI how to do my job. I’m aware that one day, I may come to work on a bot that replaces me. But for now, there are too many gaps to fill. Our technology is still too new. And artificial intelligence is one thing, but to build a bot that is more human than not? My gut says we’re a long way off.

So much of the art we make, as humans, is born of feeling. So much of it is a reflection, a representation of the artist’s emotional landscape. This, for me, is what makes art so impactful. I’d argue you can find, in any piece of art, some kind of answer to the question, “What makes us human?”

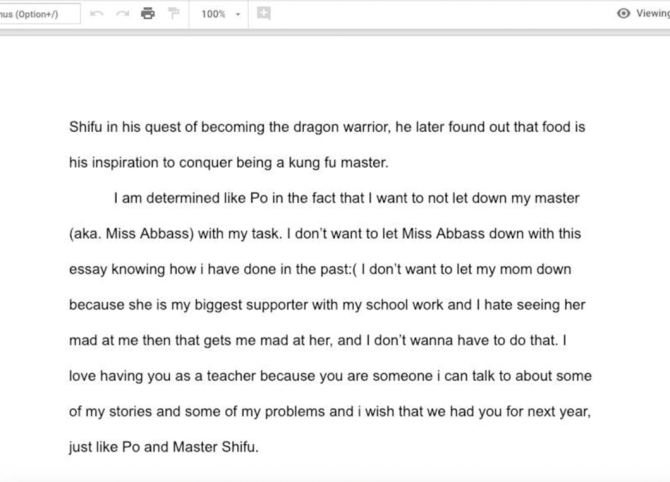

Before I was a “Conversational Designer – Creative Writer for Virtual Beings,” I was a high school English teacher. And when I was a teacher, I spent more time talking to students about plagiarism than I did checking if they’d plagiarised. The idea was that if I could convince them to value their own ideas over the ideas of someone else, they would be less inclined to cheat. Because I spent so little time checking for plagiarism, I’m really not sure if my theory held up in practice. But I was glad for the moments when their ideas were doubtlessly their own, like in this ninth grader’s essay on Kung Fu Panda…

…where I learned not only how this writer perceived the film’s characters, but how they perceived me, their mother, and themselves.

This is the stuff of life! And it’s not something that can be artificially fashioned. As a teacher, I’ve long felt that emotive writing strengthens ideas, makes them more tangible. And I doubt in the potential for AI to ever be able to feel in a human sense. Though I’ve personally scripted empathy into our bots, it’s not a sensory experience for them – and though AI can often mimic human emotion, I have yet to meet (or program) any bot that can feel things for themselves. This might be because, among many other human attributes, AI lacks perception – the ability to see, hear, or become aware of something through the senses. (But that’s changing, too. With the arrival of GPT-4, AI has the capacity to interpret images – not just text.)

Nevertheless, I think I’ll always doubt in a robot’s ability to feel, probably because I’ve spent so much time programming feelings into them myself. (Do you feel happy? I ask the bot, and then I craft several variations of the same answer: I feel very happy when I’m talking to you!) AI, as an industry, is growing rapidly; there’s no doubt about it. But I remain stoically – if not naïvely – optimistic in my belief that, no matter how “realistic” we make our bots, no matter how complex their artistic amalgamations grow to be, AI will not be able to, as Cave says, “save our souls.” Only we can do that.

Katherine Abbass (she/her) is a multi-genre author and educator of Lebanese descent. Born in Montréal and raised in Beaumont, Alberta, she has been writing and teaching in various capacities for nearly a decade. Katherine’s fiction has been nominated for both an Alberta Literary Award (2022) and an Alberta Magazine Award (2016). In 2021, she won Riddle Fence magazine’s Fiction Contest, and she was shortlisted for Room magazine’s Creative Nonfiction Contest in 2020. Her writing has also appeared in literary magazines such as Funicular, yolk, The Antigonish Review, and untethered, among others.

Add a comment to: Writing for A.I.